Once a war refugee, Soldier rises through Army’s ranks

WASHINGTON -- At Saigon’s Tan Son Nhat International Airport, 3-year-old Danielle Ngo sat in a terminal with her mother and infant sister. For hours they had waited for a plane that would take them out of Vietnam.

Then they felt a rumble.

The ceiling began to peel as the building shook. Debris fell onto terrified onlookers.

North Vietnamese had sent rockets crashing onto the sprawling airport on April 29, 1975, a day before the fall of Saigon.

“What came to my mind was just get the kids somewhere safe,” Thai-An said.

Moments after the rockets landed, Danielle, her 1-year old sister, Lan-Dinh, and their mother were rushed to the tarmac. In the distance, Thai-An heard more rockets falling onto the airport as they stood in line to board a military aircraft. “I didn’t look back,” she said.

Thai-An said they likely became one of the last Vietnamese refugees to escape the airport, which served as a military base for South Vietnamese and U.S. aircraft. They and other South Vietnamese climbed into the back of one of the final U.S. military planes to leave the battle-torn nation.

The Ngos family left the war behind them as the plane climbed over the South China Sea.

Danielle, now the executive officer to the U.S. Army inspector general in Washington, D.C., remembers little of that day when she and her family fled their homeland and the war that embroiled it. She only knows what happened from her mother’s stories.

The military plane eventually landed at a camp in the remote U.S. territory, Wake Island, about 2,300 miles west of Hawaii. They were officially refugees. There, they spent three months waiting for a country to accept them. Finally they learned that the U.S. would offer them sanctuary, her mother said.

With only a few bags of belongings, they boarded planes to camps in Hawaii and then Arkansas.

Throughout the trip, Danielle never let her sister out of her sight. At times, her mother had to carry the luggage that contained their change of clothes and diapers.

“She always [held] onto her sister’s hand,” Thai-An recalled. “She wouldn’t let go.”

They later spent several weeks in Dallas before an uncle agreed to sponsor them. All the while, her mother told her to hold onto her sister.

They finally moved into government housing in Melrose, a predominantly white suburb of Boston just north of the Mystic River. When the Ngo family migrated to America, much of the U.S. still harbored anti-war sentiments and remained apprehensive toward accepting Vietnamese refugees.

During her early years, Danielle learned to take responsibility for her sister and to respect her mother’s wisdom. Through her mother’s strength, she said, she learned to become someone who could lead Soldiers.

Distant memories

A brown and red oil painting hangs above the fireplace of Col. Danielle Ngo’s Fairfax, Virginia, home. The painting shows Thai-An as a young mother cradling baby Danielle in her arms after her birth in the South Vietnamese port town of Vung Tau.

It has been more than 46 years since the Ngos left their lives in Saigon. She only can recall the memory of her grandfather placing a dollar bill in the pocket of her blue shirt, and the name he gave her, Nhu-Nguyen, which means “wish came true” in Vietnamese. She has forgotten how to read and speak Vietnamese.

She didn’t know much about her father, except that he served as an officer in the South Vietnamese Army and trained with U.S. Special Forces. Northern Vietnamese forces eventually took him prisoner after his family left for the U.S. To this day, the family does not know his whereabouts.

In America, they lived in subsidized housing for eight years. The family had little money for new clothes and toys. For years Danielle rode a small bicycle that didn’t have a seat cushion.

When Danielle reached the seventh grade, the family moved to the affluent southern Boston suburb of Hingham along the Massachusetts Bay. As a single mother, Thai-An often could not be home to take care of her children. She had married young at age 17 and gave birth to Danielle at 18. Thai-An, still in her early 20s, had aspirations to attend college and build a career and better life for her children.

Despite only a 15-month age gap between the Ngo sisters, responsibilities often fell to Danielle, who watched over Lan-Dinh. She held her younger sister’s hand once again when they walked to school or the local YMCA, where they took swimming and gymnastics lessons. She always made sure that Lan-Dinh had something to eat when she became hungry.

In high school, Lan-Dinh played organized sports for the first time, competing in basketball and soccer before settling on joining the school’s dancing production. Danielle joined the choir and French clubs and even started her own volunteer group, where she served bread to Boston’s homeless and cared for the elderly.

“It was such an inspiration to watch her do that,” Lan-Dinh said. “I would say that was the first time she actually like led and organized something.

“Probably most of the leadership [skills] she actually learned came from the military, because in an Asian household, children did not really demonstrate any leadership. They are very obedient.”

In tribute

Although Danielle and Lan-Dinh cannot recall the fateful day in 1975, they listened to their mother’s words.

Her mother remembers seeing the uniforms of the U.S. Soldiers who welcomed them onto Wake Island. At each camp they traveled, they saw the Army fatigues. When Lan-Dinh became sick as in infant, Army nurses treated her at the island’s military hospital and learned she had been allergic to milk.

Danielle valued her life in the United States, so much that she had decided she would join the U.S. Army at 17 to repay the debt she felt she owed.

“I wanted to give something back to America, which was my country now,” Danielle said. “[America] had saved me from the war.”

At first her mother resisted. She didn’t want to risk the possibility of her eldest daughter going to war after she had sacrificed so much to escape one in Vietnam. She wanted Danielle to find a way to attend college.

Danielle, intent on enlisting, pledged that she would use the Montgomery G.I. Bill to get an education after active duty and eventually her mother agreed. With hopes of becoming a doctor, she had enlisted as an operating room technician in 1989.

She now wore the uniform of the Soldiers who gave her family safe passage.

In 1991, Danielle decided to return to her homeland alone after joining the Army. Her plane landed at Tan Son Nhat, the same airport where she and her family escaped the Vietnam War years before.

She visited her place of birth in the Ba Ria-Vung Tau province. And finally she sat with her grandfather in the family’s dusty art studio in Saigon, which the North Vietnamese renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

Each day her grandfather would ride his bicycle to the studio where they would sit inside and communicate by writing questions and answers on notepads. Her grandfather, Ngo Ngoc Tung, had taught himself English, but felt more comfortable conversing that way.

There she learned about her grandfather’s life in Vietnam, how he built his house with his own hands without the aid tools. He told her about how he taught his children how to paint and create works of art. He showed her the beautiful pieces her family had created through the years.

About a year after her visit, her grandfather died.

Thai-An shifted from job to job, first earning an associate’s degree while working as a caretaker for the elderly. She eventually earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree before finally finding work as a librarian.

Her mother instructed her children to only speak English in the household, so that she could teach herself through them. “It was a very stressful and trying time for her,” Danielle said.

By witnessing her struggle, it left an impact on her daughters.

“My mother," Danielle said. "is an incredible woman."

Following her lead

Danielle enjoyed her time as an enlisted Soldier, but remembered the promise she had made to her mother. She left active duty briefly after two years to attend the University of Massachusetts Boston in late 1991 on a scholarship to study finance. She worked at the Veterans Affairs office at her school and she later joined Boston University’s ROTC program in her second year, all while helping to care for her youngest sister, Stefanie, at home.

Lan-Dinh, inspired by Danielle’s commitment, attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

In 1994 Danielle graduated from UMass Boston and earned her commission as a combat engineer officer.

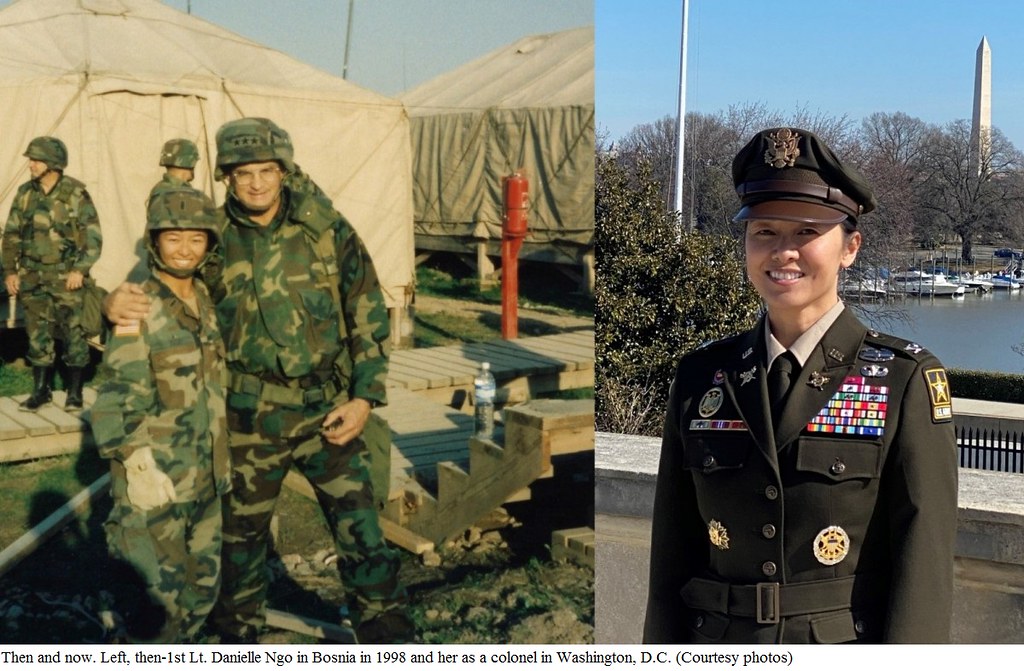

As a young captain, she saw wars on fronts vastly different from the one she escaped in her childhood. She traveled to Bosnia in 1998 as a company executive officer. Then, 18 months after America watched the twin towers fall, she deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Being the lone woman in units dominated by men had its challenges, but fueled her to train harder. As she climbed the officer ranks, she kept a stern level of professionalism, but with humility.

The sisters’ military careers crossed paths in 1998 when both received assignments at Fort Hood, Texas, in 1998. They lived together for three years until Lan-Dinh left active duty in 2001. During unit dinners Lan-Dinh saw the impact her sister had on her troops. Danielle would even invite Soldiers to her house for Thanksgiving dinner.

“I just [knew] they loved her,” Lan-Dinh said. “When they're there with their families … You can see they have a huge amount of respect for her.”

Danielle listens to Soldiers’ concerns. She values the opinions of her non-commissioned officers, Lan-Dinh said.

Danielle had opted to become a female engineer, in part because she felt the career presented the toughest challenge for a female Soldier.

In 2001, prior to the events on 9/11, she became the first female company commander in a combat engineer battalion directly assigned to a combat brigade, which was 4th Infantry Division's 1st Brigade. In 2003, the brigade, originally designated to go into Iraq through Turkey, ended up following the 3rd Infantry Division into Iraq through Kuwait.

She spent the first sixth months as the brigade's logistics officer helping equip a combat brigade so it could convoy from Kuwait to Tikrit, Iraq. The length of the convoy spanned over 800 kilometers. Her unit often had to improvise as the U.S. military had not established any facilities yet and had to fight in austere conditions.

Males and females bunked together. They made makeshift showers and dug burn pits. During the days she endured sweltering heat while keeping a vigil for enemy fire. “It was almost impossible to sleep during the day,” Danielle said. “It got so hot.”

U.S. officials would later credit her unit, the 4th Infantry Division, with being among those who helped capture Saddam Hussein. Danielle would go on to deploy to Afghanistan to help plan the surge, command an engineering battalion at Fort Carson, Colorado, and work as a military assistant to the chairman of the NATO Military Committee.

She eventually became the commander of the 130th Engineer Brigade at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. There she provided combat and construction support across the Pacific, deploying Soldiers to 17 countries. For example, her team helped coordinate the civil service agreement between the U.S. and the government of Palau to bring teams of Army craftsman and laborers for crucial construction projects in the remote Pacific island nation.

It has been more than 46 years since the Ngos left their lives in Saigon. She only can recall the memory of her grandfather placing a dollar bill in the pocket of her blue shirt, and the name he gave her, Nhu-Nguyen, which means “wish came true” in Vietnamese. She has forgotten how to read and speak Vietnamese.

She didn’t know much about her father, except that he served as an officer in the South Vietnamese Army and trained with U.S. Special Forces. Northern Vietnamese forces eventually took him prisoner after his family left for the U.S. To this day, the family does not know his whereabouts.

In America, they lived in subsidized housing for eight years. The family had little money for new clothes and toys. For years Danielle rode a small bicycle that didn’t have a seat cushion.

When Danielle reached the seventh grade, the family moved to the affluent southern Boston suburb of Hingham along the Massachusetts Bay. As a single mother, Thai-An often could not be home to take care of her children. She had married young at age 17 and gave birth to Danielle at 18. Thai-An, still in her early 20s, had aspirations to attend college and build a career and better life for her children.

Despite only a 15-month age gap between the Ngo sisters, responsibilities often fell to Danielle, who watched over Lan-Dinh. She held her younger sister’s hand once again when they walked to school or the local YMCA, where they took swimming and gymnastics lessons. She always made sure that Lan-Dinh had something to eat when she became hungry.

In high school, Lan-Dinh played organized sports for the first time, competing in basketball and soccer before settling on joining the school’s dancing production. Danielle joined the choir and French clubs and even started her own volunteer group, where she served bread to Boston’s homeless and cared for the elderly.

“It was such an inspiration to watch her do that,” Lan-Dinh said. “I would say that was the first time she actually like led and organized something.

“Probably most of the leadership [skills] she actually learned came from the military, because in an Asian household, children did not really demonstrate any leadership. They are very obedient.”

In tribute

Although Danielle and Lan-Dinh cannot recall the fateful day in 1975, they listened to their mother’s words.

Her mother remembers seeing the uniforms of the U.S. Soldiers who welcomed them onto Wake Island. At each camp they traveled, they saw the Army fatigues. When Lan-Dinh became sick as in infant, Army nurses treated her at the island’s military hospital and learned she had been allergic to milk.

Danielle valued her life in the United States, so much that she had decided she would join the U.S. Army at 17 to repay the debt she felt she owed.

“I wanted to give something back to America, which was my country now,” Danielle said. “[America] had saved me from the war.”

At first her mother resisted. She didn’t want to risk the possibility of her eldest daughter going to war after she had sacrificed so much to escape one in Vietnam. She wanted Danielle to find a way to attend college.

Danielle, intent on enlisting, pledged that she would use the Montgomery G.I. Bill to get an education after active duty and eventually her mother agreed. With hopes of becoming a doctor, she had enlisted as an operating room technician in 1989.

She now wore the uniform of the Soldiers who gave her family safe passage.

In 1991, Danielle decided to return to her homeland alone after joining the Army. Her plane landed at Tan Son Nhat, the same airport where she and her family escaped the Vietnam War years before.

She visited her place of birth in the Ba Ria-Vung Tau province. And finally she sat with her grandfather in the family’s dusty art studio in Saigon, which the North Vietnamese renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

Each day her grandfather would ride his bicycle to the studio where they would sit inside and communicate by writing questions and answers on notepads. Her grandfather, Ngo Ngoc Tung, had taught himself English, but felt more comfortable conversing that way.

There she learned about her grandfather’s life in Vietnam, how he built his house with his own hands without the aid tools. He told her about how he taught his children how to paint and create works of art. He showed her the beautiful pieces her family had created through the years.

About a year after her visit, her grandfather died.

Thai-An shifted from job to job, first earning an associate’s degree while working as a caretaker for the elderly. She eventually earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree before finally finding work as a librarian.

Her mother instructed her children to only speak English in the household, so that she could teach herself through them. “It was a very stressful and trying time for her,” Danielle said.

By witnessing her struggle, it left an impact on her daughters.

“My mother," Danielle said. "is an incredible woman."

Following her lead

Danielle enjoyed her time as an enlisted Soldier, but remembered the promise she had made to her mother. She left active duty briefly after two years to attend the University of Massachusetts Boston in late 1991 on a scholarship to study finance. She worked at the Veterans Affairs office at her school and she later joined Boston University’s ROTC program in her second year, all while helping to care for her youngest sister, Stefanie, at home.

Lan-Dinh, inspired by Danielle’s commitment, attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

In 1994 Danielle graduated from UMass Boston and earned her commission as a combat engineer officer.

As a young captain, she saw wars on fronts vastly different from the one she escaped in her childhood. She traveled to Bosnia in 1998 as a company executive officer. Then, 18 months after America watched the twin towers fall, she deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Being the lone woman in units dominated by men had its challenges, but fueled her to train harder. As she climbed the officer ranks, she kept a stern level of professionalism, but with humility.

The sisters’ military careers crossed paths in 1998 when both received assignments at Fort Hood, Texas, in 1998. They lived together for three years until Lan-Dinh left active duty in 2001. During unit dinners Lan-Dinh saw the impact her sister had on her troops. Danielle would even invite Soldiers to her house for Thanksgiving dinner.

“I just [knew] they loved her,” Lan-Dinh said. “When they're there with their families … You can see they have a huge amount of respect for her.”

Danielle listens to Soldiers’ concerns. She values the opinions of her non-commissioned officers, Lan-Dinh said.

Danielle had opted to become a female engineer, in part because she felt the career presented the toughest challenge for a female Soldier.

In 2001, prior to the events on 9/11, she became the first female company commander in a combat engineer battalion directly assigned to a combat brigade, which was 4th Infantry Division's 1st Brigade. In 2003, the brigade, originally designated to go into Iraq through Turkey, ended up following the 3rd Infantry Division into Iraq through Kuwait.

She spent the first sixth months as the brigade's logistics officer helping equip a combat brigade so it could convoy from Kuwait to Tikrit, Iraq. The length of the convoy spanned over 800 kilometers. Her unit often had to improvise as the U.S. military had not established any facilities yet and had to fight in austere conditions.

Males and females bunked together. They made makeshift showers and dug burn pits. During the days she endured sweltering heat while keeping a vigil for enemy fire. “It was almost impossible to sleep during the day,” Danielle said. “It got so hot.”

U.S. officials would later credit her unit, the 4th Infantry Division, with being among those who helped capture Saddam Hussein. Danielle would go on to deploy to Afghanistan to help plan the surge, command an engineering battalion at Fort Carson, Colorado, and work as a military assistant to the chairman of the NATO Military Committee.

She eventually became the commander of the 130th Engineer Brigade at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. There she provided combat and construction support across the Pacific, deploying Soldiers to 17 countries. For example, her team helped coordinate the civil service agreement between the U.S. and the government of Palau to bring teams of Army craftsman and laborers for crucial construction projects in the remote Pacific island nation.

No comments:

Post a Comment